A new era in tackling cancer

February 12, 2024 | Dubai, United Arab Emirates

February 12, 2024 | Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Developments in scientific research could help bring about a sea-change in how we fight cancer. But meeting the challenges posed by the disease will also involve serious efforts from those outside the lab.

Cancer is one of the biggest health issues facing the world today. It can have a devastating impact on the lives of individuals and families, as well as causing major problems for healthcare systems and economies.

In numerical terms, it’s the second-leading cause of death worldwide, responsible for ten million deaths – that’s one in six – in 2020. There were an estimated 18.1 million new cancer cases globally in 2020[1], including 9.3 million cases in men and 8.8 million in women.

The costs of cancer care are huge and are expected to exceed US$ 240 billion by 2030[2] in the US alone. Cancer also has a major impact on economies due its effects on people’s finances and capacity to work. Analysis published in 2023 examined the economic cost of 29 cancers in 204 countries and territories, based on productivity losses and the cost of treatment[3]. The researchers estimated that between 2020 and 2050, cancer would cost the global economy US$ 25.2 trillion in international dollars – equivalent to a yearly tax of 0.55% on global GDP.

Who gets cancer?

As discussed in our previous Insights article on combatting cancer, cancer doesn’t refer to a single condition. The term is used to describe a large group of diseases that occur when cells start to grow abnormally and invade other parts of the body. These can affect many different organs and tissues. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the most common cause of cancer death in 2020 was lung cancers (1.8 million), followed by cancers of the colon and rectum (916,000) and liver (830,000)[4].

The disease is generally more common in richer countries. This can be seen by comparing cancer rates, standardized for age, between different areas using the UN’s Human Development Index (HDI). Statistics from the Global Cancer Observatory (GCO) show that in 2020, there were 8.9 million cases of cancer in areas with a very high HDI, compared to about 650,000 in those with a low HDI score. There was a big difference between the age-standardized rates too: there were 295.3 cases of cancer per 100,000 people in highly developed areas, compared to 115.7 in areas with low development[5].

Looking at individual countries, in 2020, the three with the highest rate of new cancer cases were Denmark (334.9 per 100,000 people), Ireland (326.6) and Belgium (322.8). Meanwhile, the lowest age-standardized rates were seen in Niger (76.4 per 100,000 people), Gambia (79.3) and Nepal (80.0)[6].

Global trends

Cancer is on the rise worldwide, with data from the GCO indicating that by 2040, cases will have grown to 29 million.

Because the risk of cancers greatly increases with age, it is sometimes perceived as mainly being a problem for affluent societies where people tend to live longer. But this impression is now well out of date. According to GCO data, the rate of increase in cancer diagnoses is now significantly higher in less developed countries[7].

As far back as 2010, the then UN director general, Margaret Chan, highlighted the challenges caused by the shift of the disease burden of cancer from wealthy to less affluent countries[8]. Chan highlighted that about 70% of cancer deaths worldwide each year took place in the developing world, underlining how “a disease once associated with affluence now places its heaviest burden on poor and disadvantaged populations”.

The problems that Chan spoke of more than a decade ago are getting worse. The WCRF points out that cases and deaths from cancer are increasing significantly more in low and middle income countries, and most rapidly in countries with a low HDI score. Globocan estimates increases of more than 90% in both incidence and mortality rates of cancer in low HDI countries between 2020 and 2040, compared to substantially lower increases (32.2% and 42.5% respectively) in those with a very high HDI score[9].

Two of the key factors highlighted were aging populations, and the spread of unhealthy lifestyles – both of which remain highly significant. As people live longer across the world, their risk of developing cancers correspondingly increases.And while in many richer countries, awareness of the importance of lifestyle factors in preventing disease is growing, issues such as smoking and obesity are increasing in the developing world.

Eighty per cent of the world’s 1.3 billion tobacco users live in low and middle income countries, according to the WHO[10]. While a report from the Overseas Development Institute found that there were almost twice as many obese people in poor countries as rich ones[11]. The WHO says that overweight and obesity are now on the rise in low- and middle-income countries, especially in urban settings. Since 2000, the number of overweight children under five has increased by nearly 24% percent in Africa, while in 2019, almost half of children under five who were overweight or obese lived in Asia[12].

Lower access to healthcare services, such as cancer screening and treatment, is also an important contributory factor. Researchers analyzing this subject last year commented that: “The survival rate of different cancers is lower in LMICs as they lack early detection programs, disease prevention, cost-effective treatment and oncologic infrastructure.”[13]

Another recent trend is a rise in cancer among younger people. In a study for the BMJ Oncology Journal last year which “upends received wisdom”, researchers found a 79% increase in new cancer cases among the under 50s over the past three decades[14].

Breast cancer accounted for the largest number of these cases, while the fastest rates of growth were seen in cancers of the trachea and prostate. Worryingly, the researchers predicted that early onset cancer cases will increase by a further 31% by 2030, with people in their 40s most at risk.

Preventing and treating cancer

While the reasons for the increase in cancer among younger people are not fully understood, the BMJ Oncology researchers highlighted lifestyle factors such as diet as a possible part of the explanation.

These are relevant to many other cancer cases, too. The WHO says that between 30% and 50% of cancers are preventable and highlights the importance of addressing risk factors including the consumption of alcohol and tobacco, obesity, and physical inactivity. Infections, environmental pollution, radiation and exposure to carcinogens (such as asbestos) at work can also add to the risk of someone developing cancer.

Alongside tackling issues such as these, medical interventions to screen for and treat cancer are also essential. Treatment options include surgery, drugs and radiotherapy, with the most effective approaches varying depending on the type of cancer. The WHO says that many common cancers (such as breast cancer, colorectal cancer, cervical cancer, and oral cancer) have “high cure probabilities when detected early and treated according to best practices”[15].

In many places, improvements in diagnosing and treating cancer, as well as preventing it, are leading to significantly fewer deaths. A 2023 report from the American Cancer Society, for example, found that the death rate from cancer in the US had fallen by a third (33%) since 1991[16]. As well as reductions in smoking and improvements in screening, the journal said this progress “reflects advancements in treatment”. In particular, it highlighted the impact of advances in treatment in contributing to “rapid declines” in deaths from leukemia, melanoma, and kidney cancer, as well as “accelerated declines” in lung cancer mortality.

New research developments

Research into cancer treatments is always progressing. In recent years there has been an exciting change of pace that many believe is creating a brighter landscape for cancer sufferers.

An article in the New York Times in 2023 said the development of cancer drugs is now happening so rapidly that for some patients it is “outpacing the growth of cancer cells inside their bodies”, making it “more like a chronic disease than a one-time catastrophic event”[17].

This is not down to any single development, but a variety of different advances that are exerting downward pressure on cancer mortality in new ways and at the same time. Until recently, for example, it was believed that it was almost impossible to cure patients with metastatic cancer – where the disease has spread to other parts of the body. But some are now being cured completely by new drugs, and others are able to stay one step ahead of their illness due to ongoing new discoveries.

So, what were these developments? Traditionally, many cancer treatments have been based on chemotherapy or radiotherapy – where drugs or radiation respectively are used to kill cancer cells. These can be very effective, but their success depends on the type of cancer and how far it has progressed, and they can both have major side effects by also damaging healthy cells.

In contrast, many of the most exciting recent advances in cancer treatment have been in the field of immunotherapy – which harnesses the power of the body’s immune system to destroy cancer cells.

Checkpoint inhibitor drugs are one example. The immune system naturally includes ‘checkpoints’ that stop it from attacking healthy cells, and some cancer cells make use of this feature to evade the body’s defenses. Checkpoint inhibitors work by allowing the immune system to recognize and attack the cancer cells. The first such drug was approved in 2011, and it has since been joined by many more. The US Government’s National Cancer Institute says checkpoint inhibitor drugs can be used to treat many different cancers including breast cancer, lung cancer and rectal cancer[18] – and for some people, they have remarkable success. In one US-based trial in 2022, 14 patients with rectal cancer who were given a checkpoint inhibitor saw the disease disappear completely – with no need for surgery, radiation or chemotherapy[19].

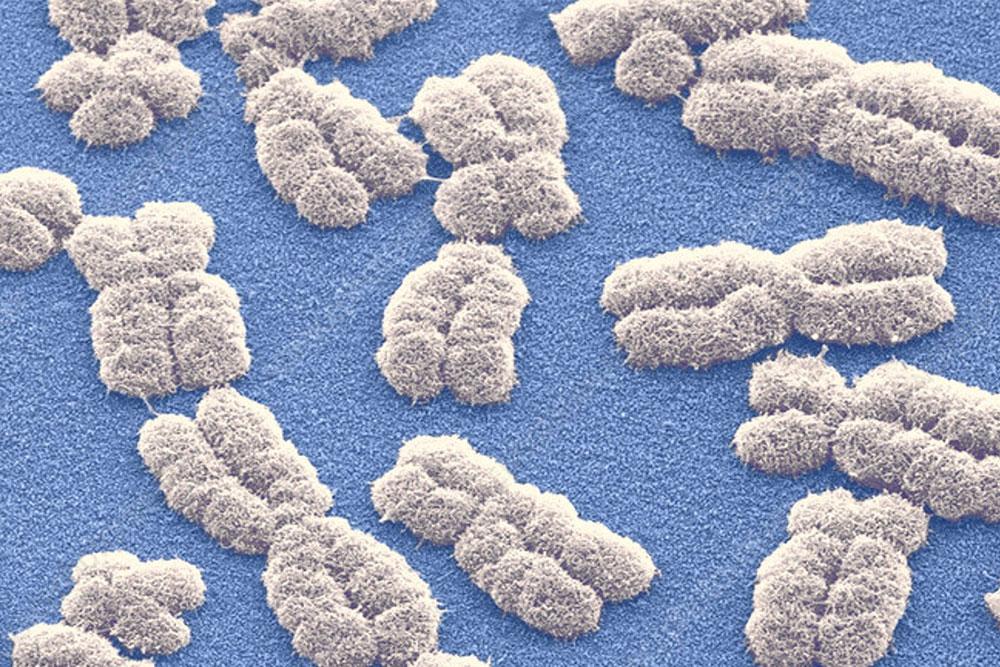

Other encouraging developments within immunology include adoptive cell therapies. These involve using a patient’s own immune cells to fight their cancer – sometimes by boosting their numbers and sometimes by genetically adapting them to enhance their capabilities[20].

One such approach is Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T cell therapy, which involves extracting and modifying T-cells from a patient before infusing back into their blood. The approach has been successfully used to treat patients with some blood cancers (such as leukemia). While the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently told several drugmakers to warn that their CAR-T therapies could increase the risk of secondary cancers, it noted that the benefits still outweighed this risk[21]. And according to a recent analysis, the market for CAR-T is expected to grow at a “considerable” rate in the coming years[22].

Photo Credit © Steve Gschmeissner / Science Photo Library

Vaccines that stimulate the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells are yet another area of immunological research that is generating great interest. Last year, for example, the UK Government announced a major partnership with the German company BioNTech – which previously developed a groundbreaking COVID-19 vaccine with Pfizer – that aims to provide up to 10,000 patients with “precision cancer immunotherapies” by 2030[23]. BioNTech will set up new laboratories in the UK to support the development of such treatments.

Aside from immunology, another promising area of cancer treatment research is antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs). These treatments combine the traditional destructive power of chemotherapy with an antibody that specifically targets tumor cells. This means the chemotherapy is focused specifically at the cancer cells, helping avoid damaging side effects. Interest in ADCs is rapidly growing. They have been successfully used to treat breast cancer[24] and as of October 2023, the US Food and Drug Administration had approved the use of 15 different kinds[25].

Drug manufactures appear to see big potential in this type of drug. Early in 2024, Johnson and Johnson announced it would acquire the ADC specialist Ambrx Biopharma for US$2 billion, and the Anglo-Swedish firm AstraZeneca is partnering with Japan’s Daiichi Sankyo on the development of two ADCs[26].

The new breed of cancer treatments tend to share common characteristics: they are better aligned with patients’ individual situations and therefore kinder to their bodies. AstraZeneca, for example, is also researching radioconjugates – where, in similar fashion to ADCs, antibodies or other vehicles are used to target radiotherapy agents specifically at tumor cells and offer more tailored treatment for patients.

Another exciting new development is a biology-guided radiation machine, the Reflexion X1, which makes use of positron emission tomography (PET) technology to direct radiotherapy more precisely at cancer cells. The first patient completed treatment using the machine last year.[27]

The rapid progress being made in scientists’ understanding of cancers is creating real optimism that we are entering a new era in the fight against the diseases.

Shared vision

What these advances show is that tackling cancer involves many different areas of expertise. This is reflected in the work that Abdul Latif Jameel Health is involved in across the globe.

The Abdul Latif Jameel Clinic for Machine Learning in Health (Jameel Clinic) at MIT, for example, is at the forefront of international cancer research. In 2023, Jameel Clinic researchers unveiled an AI model called ‘Sybil’ that can detect future lung cancer risk[28]. Sybil’s deep-learning model takes a personalized approach to assessing each patient’s risk of lung cancer based on CT scans. Low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) scans of the lung are currently the most common way patients are screened for lung cancer with the hope of finding it in the earliest stages, when it can still be surgically removed. Sybil takes the screening a step further, analyzing the LDCT image data without the assistance of a radiologist to predict the risk of a patient developing a future lung cancer within six years.

The Jameel Clinic is also partnering with the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre (KFSH&RC) in Saudi Arabia to roll out its Mirai technology in the country. Mirai is a pioneering AI tool developed by Regina Barzilay, faculty lead for AI at the Jameel Clinic, that can predict breast cancer up to five years earlier, and more accurately, than current mainstream screening techniques. A non-invasive, deep-learning algorithm that can predict breast cancer using only a patient’s mammogram, Mirai is equally effective across different races and ethnicities.

These advances follow on from previous pioneering work at MIT to develop a new model to help identify mutations that drive cancer. The model rapidly scans the entire genome of cancer cells and can identify mutations that occur more frequently than expected, suggesting that they are driving tumor growth. This could provide valuable information to help researchers identify targets for new drugs.

“The number of cancer sufferers is growing every year. Far from being a problem for wealthy countries, it is increasingly affecting people in less developed markets, too, particularly in the global south”, says Dr. Akram Bouchenaki, Chief Executive Officer of Abdul Latif Jameel Health. “By investing in new innovations and supporting breakthrough research, we in the private sector can help maintain the pipeline of groundbreaking treatments with the potential to turn the tables on cancer. In so doing, we can offer fresh hope to patients worldwide, regardless of their place of birth, income level or social status.”

This kind of collaborative approach is rarely straightforward. But it will be essential if the world is to make progress in tackling cancer. The World Cancer Day campaign in February 2024 underlined the strength of global support for meeting such challenges.

The initiative’s ambition for a cancer-free world may seem daunting. But many will draw inspiration from its call for everyone to have equal access to life-saving cancer care, regardless of their circumstances.

[1] https://www.wcrf.org/cancer-trends/worldwide-cancer-data/

[2] https://aacrjournals.org/cebp/article/29/7/1304/72361/Medical-Care-Costs-Associated-with-Cancer

[3] https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/fullarticle/2801798

[4] https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer

[5] https://www.wcrf.org/cancer-trends/cancer-rates-human-development-index/

[6] https://www.wcrf.org/cancer-trends/global-cancer-data-by-country/

[7] https://www.wcrf.org/differences-in-cancer-incidence-and-mortality-across-the-globe/

[8] https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/cancer-in-developing-countries-facing-the-challenge

[9] https://www.wcrf.org/differences-in-cancer-incidence-and-mortality-across-the-globe/

[10] https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco

[11] https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/jan/03/obesity-soars-alarming-levels-developing-countries

[12] https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

[13] https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1124473/full#B6

[14] https://www.bmj.com/company/newsroom/global-surge-in-cancers-among-the-under-50s-over-past-three-decades

[15] https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer

[16] https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.3322/caac.21763

[17] https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/16/opinion/cancer-treatment-disparities.html

[18] https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types/immunotherapy/checkpoint-inhibitors

[19] https://www.mskcc.org/news/rectal-cancer-disappears-after-experimental-use-immunotherapy

[20] https://www.cancerresearch.org/treatment-types/adoptive-cell-therapy

[21] https://edition.cnn.com/2024/01/24/health/fda-car-t-therapies-secondary-cancer-risk/index.html

[22] https://www.delveinsight.com/report-store/chimeric-antigen-receptor-car-t-cell-therapy-market

[23] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/major-agreement-to-deliver-new-cancer-vaccine-trials

[24] https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/EDBK_390094

[25] https://broadpharm.com/blog/ADC-Approval-up-to-2023

[26] https://www.ft.com/content/0cb609da-f6b0-4d79-aa84-c972dd60b34e

[27] https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20230823800478/en/World’s-First-Cancer-Patient-Treated-with-RefleXion’s-Breakthrough-SCINTIX-Biology-guided-Radiotherapy

[28] https://news.mit.edu/2023/ai-model-can-detect-future-lung-cancer-0120

Related Articles

For press inquiries click here, or call +971 4 448 0906 (GMT +4 hours UAE). For public inquiries click here.